Sake 🍶: Swift-powered Command Management - Part II

In the first part of this series, we covered the basics of Sake, a CLI tool that lets you write and run tasks in Swift for your projects, instead of shell scripts.

In this second and last part, you’ll learn how to use Sake for managing complex automations tasks, such as testing and creating new GitHub releases. To finalize, you’ll learn how to use GitHub Actions to automate your workflows running Sake.

The sample project for this part is the same as the first one, so you can follow along with the code.

Adding More Command Groups

As covered in the first part, the Sakefile is the entry point of the SakeApp. It contains a macro attached to the @main struct, grouping all your commands in a single place.

This doesn’t mean, however, that you can’t create more command groups. In fact, you can create as many as you want, and separate them in different files. In the sample project, you can find two files that contain command groups: TestCommands.swift and ReleaseCommands.swift.

// TestCommands.swift

@CommandGroup

struct TestCommands {

public static var test: Command { ... }

}

// ReleaseCommands.swift

@CommandGroup

struct ReleaseCommands {

public static var release: Command { ... }

}To make them available to the Sake CLI, it’s not enough to just create these files. The groups they declare need to be added to the Sakefile configuration:

// Sakefile.swift

@main

@CommandGroup

struct Commands: SakeApp {

public static var configuration: SakeAppConfiguration {

SakeAppConfiguration(

commandGroups: [

TestCommands.self, // <--

ReleaseCommands.self, // <--

]

)

}

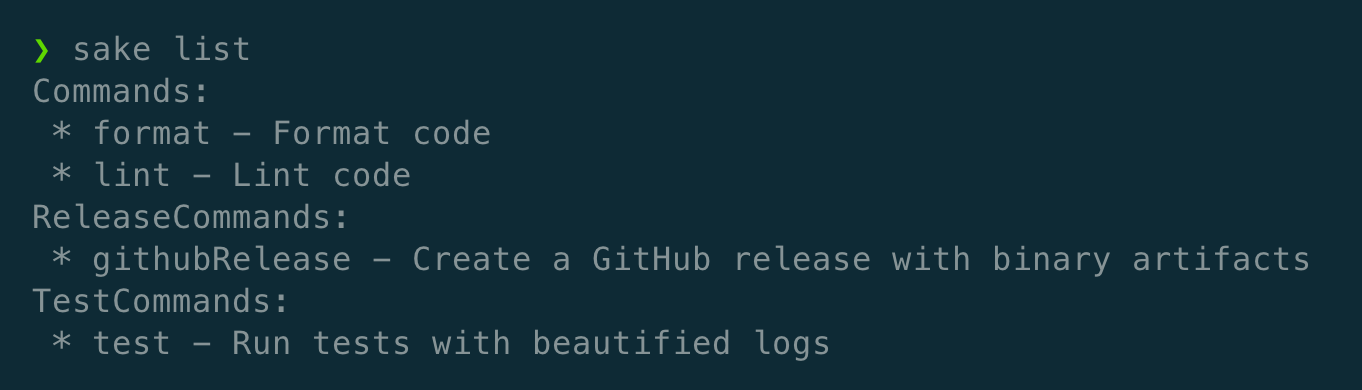

}Now, after you add them to the Sakefile, you can see them listed when running the list command:

After having defined and added them, you can now focus on the commands themselves.

The Test Command

As the first part explained, commands are the individual tasks that you can run. The first one we’ll look into it is the smaller and simpler one: the test command.

@CommandGroup

struct TestCommands {

public static var test: Command {

Command(

description: "Run tests with beautified logs",

dependencies: [MiseCommands.ensureXcbeautifyInstalled],

run: { ... }

)

}

}We start by initializing a Command, providing a description that is displayed when listing the command, and an array of depedencies. In this case, it dependends on a command that uses mise to install xcbeautify, or just skips the installation if it’s already installed.

The run closure is where the actual logic of the command is written. We separated into another piece of code to make it more readable:

run: { context in

try interruptableRunAndPrint(

bash: "swift test | (MiseCommands.miseBin(context)) exec -- xcbeautify --disable-logging",

interruptionHandler: context.interruptionHandler

)

}This code looks more complex than it is. There are three main parts:

- The

interruptableRunAndPrintfunction wraps SwiftShell to spin a subprocess and execute an asynchronous command, allowing it to be interrupted withctrl+c. Notice how the interruption handler from Sake’s context is passed to it; - The core of this command is

swift test, which uses SPM to run the tests; - The output of the tests is piped into xcbeautify, which formats the logs to make them more readable. xcbeautify is executed through mise, so prefix

/path/to/mise exec --to the command.

Now, when running sake test, you should see this output:

Notice how xcbeautify is installed automatically before running the tests.

The Release Command

The release command is much more complex, and this section will only focus on the most interesting parts of it.

Private Commands

To start, notice how you can define a command that depends on other commands, but without having a run closure at all. This is a great way to make your commands more modular and reusable between different parent commands.

@CommandGroup

struct ReleaseCommands {

public static var githubRelease: Command {

Command(

description: "Create a GitHub release with binary artifacts",

dependencies: [

bumpVersion,

buildReleaseArtifacts,

createAndPushTag,

draftReleaseWithArtifacts,

]

)

}

}The commands in the dependencies array don’t need to be public, as they’re not executed directly by the user, but only through the parent githubRelease command.

Mixing with the Argument Parser

In the bumpVersion command, you can notice how it is possible to leverage the Swift Argument Parser to command arguments, which are available in the context parameter. In this case, the command requires a version argument to bump the project to.

To do so, a type that conforms to the ParsableCommand protocol is defined:

struct ReleaseArguments: ParsableArguments {

@Argument(help: "Version number")

var version: String

func validate() throws {

guard version.range(of: #"^d+.d+.d+$"#, options: .regularExpression) != nil else {

throw ValidationError("Invalid version number. It should be in the format 'x.y.z'")

}

}

}The ReleaseArguments type contains only one required argument, the version string. To ensure it’s a valid version number, the validate method is overridden to check for the format using a regular expression.

Then, in both skipIf and run closures, the three lines below are enough to parse, validate and use the version argument:

let arguments = try ReleaseArguments.parse(context.arguments)

try arguments.validate()

let version = arguments.versionThis way, you can use the version variable in the rest of the command logic. The command will write a new version to a file in the parent directory:

let versionFilePath = "(context.projectRoot)/Sources/Version.swift"

let versionFileContent = """

// This file is autogenerated. Do not edit.

let cowsayCLIVersion = "(version)"

"""

try versionFileContent.write(

toFile: versionFilePath,

atomically: true,

encoding: .utf8

)Using the Context Storage

The next command, buildReleaseArtifacts, takes care of building the executable target for the different architectures on the macOS platform. In the skipIf closure, it checks which build artifacts already exist for a given version and architecture, and skips the build if they already exist.

One interesting bit there, is that the command makes use of the context storage to keep a list of artifacts that were previously built:

let existingArtifactTriples = targetsWithExistingArtifacts

.map(.triple)

context.storage["existing-artifacts-triples"] = existingArtifactTriplesThen, in the run closure, it uses the storage to check if building an artifact is really necessary:

let existingArtifactsTriples = context.storage["existing-artifacts-triples"] as? [String] ?? []

for target in Constants.buildTargets {

if existingArtifactsTriples.contains(target.triple) {

print("Skipping (target.triple) as artifacts already exist".ansiBlue)

continue

}

// Continue building the artifact...

}Tagging the Release

After bumping the version and building the executables, the createAndPushTag command will create a new tag in the Git repository, with the version number, and then push it.

As it’s safe to assume that git is available, the command doesn’t need to check for its presence, and only calls git via SwiftShell to execute a few git operations:

print("Creating and pushing tag (version)".ansiBlue)

try runAndPrint("git", "tag", version)

try runAndPrint("git", "push", "origin", "tag", version)

try runAndPrint("git", "push") // push local changes like version bumpPublishing the Release

The final step is to create the release on GitHub, with the binaries as assets, and this is where the draftReleaseWithArtifacts command comes in.

The last tool managed by mise, after SwiftFormat and xcbeautify, is gh, the GitHub CLI tool. Just as exemplified in Pedro’s distributing Swift CLIs post, it’s very useful when interacting with GitHub from the command line. In contrast to Pedro’s post, instead of using gh from a bash script, we’ll use it from a subprocess through SwiftShell, as with the previous tools.

After making sure that gh is installed in a dependency step, and checking in the skipIf closure that the release for the current version doesn’t exist yet, go ahead with creating the release. First, declare the variables for the gh command arguments: a tag and a title based on the version number, and a string with the path for the build artifacts:

let tagName = arguments.version

let releaseTitle = arguments.version

let artifactsPaths = Constants.buildTargets

.map { target in

executableArchivePath(target: target, version: tagName)

}

.joined(separator: " ")Then, run gh release create with the arguments you just declared:

let ghReleaseCommand = try """

(MiseCommands.miseBin(context)) exec -- gh release create

(tagName) (artifactsPaths)

--title '(releaseTitle)'

--verify-tag

--generate-notes

"""

try runAndPrint(bash: ghReleaseCommand)If you prefer to keep the release as a draft, and publish it manually later, you can pass also the --draft flag.

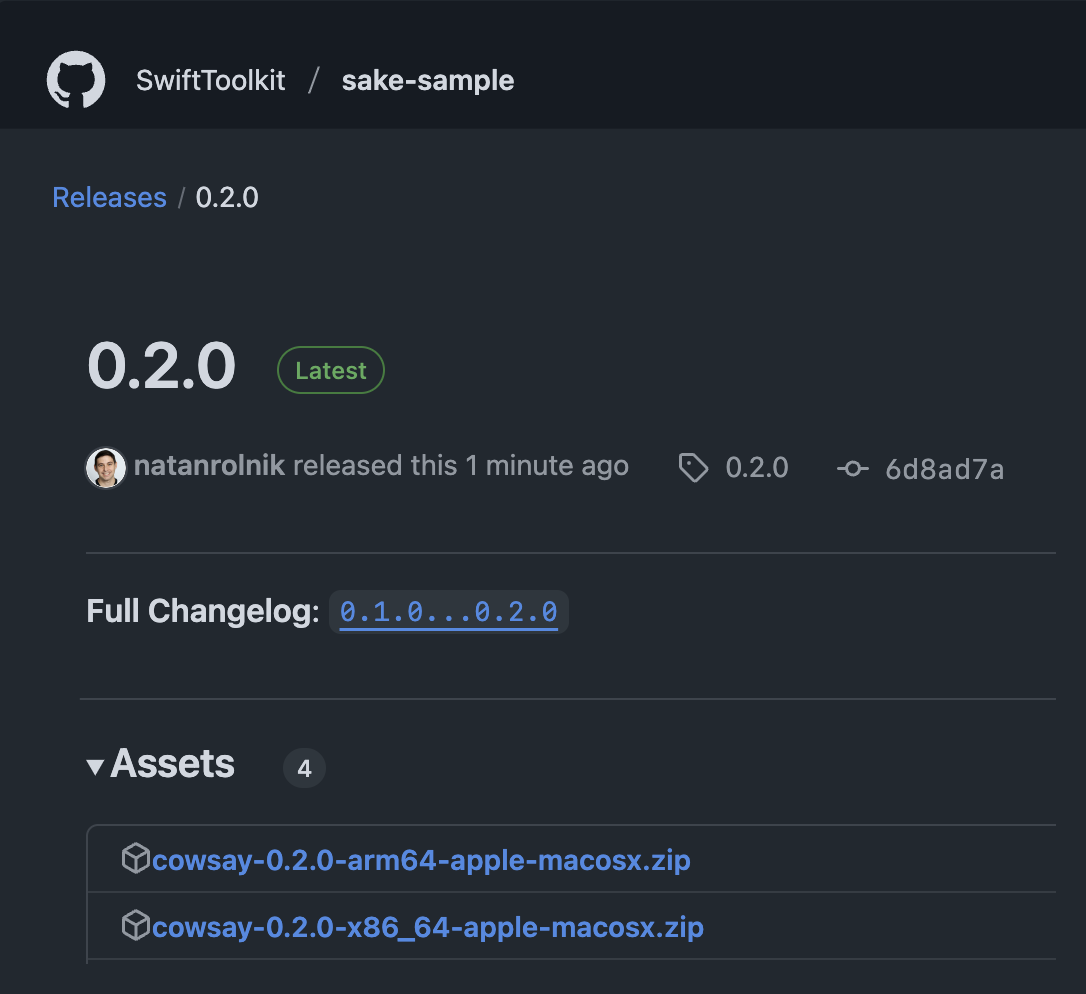

And when running the sake githubRelease command 🥁🥁🥁

And you can see the release created on GitHub, including the binaries as assets:

Running from GitHub Actions

There is one final bit of automation that can be added to the release process: running Sake from a GitHub Action.

The author of Sake, Vasiliy Katouff, already thought about this, and created a Setup Sake action.

With that action, to compose a workflow to run Sake, you’ll need to have 3 steps:

- Checkout the code

- Setup Sake

- Run the commands via Sake

Don’t forget to add also GITHUB_TOKEN environment variable:

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}And with that, here’s a sample workflow that runs the test or the lint commands:

name: Checks

on:

# add your triggers here, such as push or pull_request

env:

GITHUB_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

jobs:

build-and-test:

runs-on: macos-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: kattouf/setup-sake@v1

- name: Run tests

run: sake test

lint:

runs-on: macos-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: kattouf/setup-sake@v1

- name: Run lint

run: sake lintExplore Further

Thanks again to Vasiliy for his help with the last part of this series!

We hope you enjoyed this series, and feel empowered to write your projects’ automation tasks in Swift with Sake!

If you have any feedback for this series, you can ping Vasiliy on Mastodon, or ping us on X @SwiftToolkit or Mastodon!

See you at the next post. Have a good one!

View the sample project on GitHub

View the sample project on GitHub